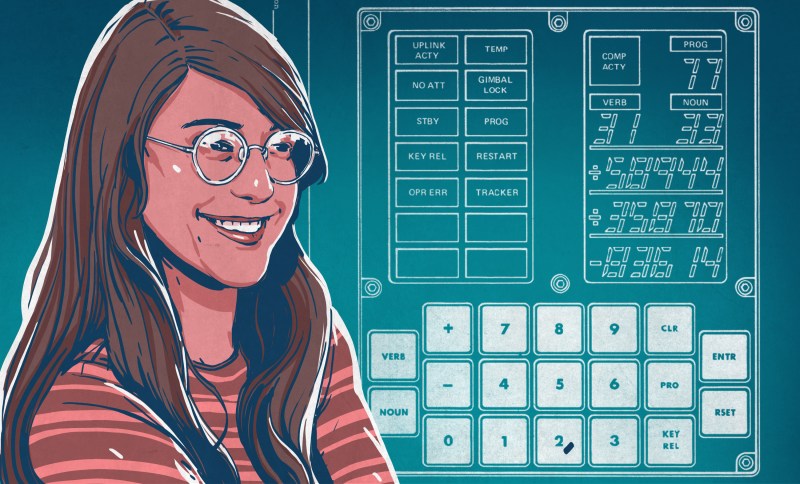

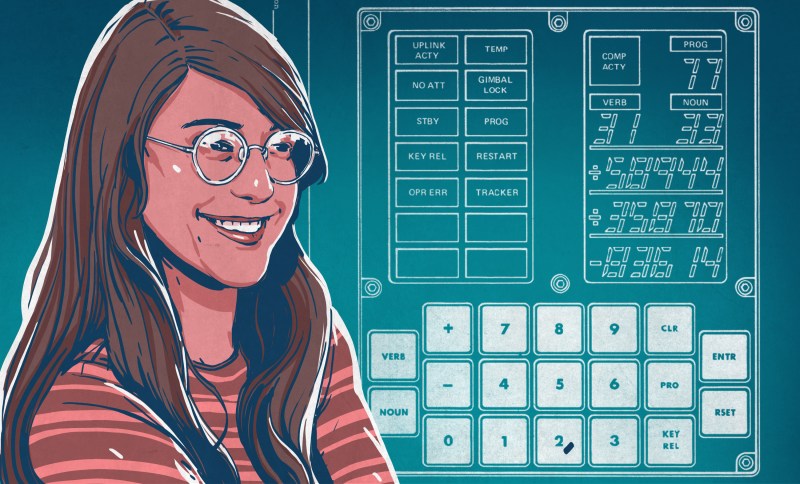

If you were to create a short list of women who influenced software engineering, one of the first picks would be Margaret Hamilton. The Apollo 11 source code lists her title as “PROGRAMMING LEADER”. Today that title would probably be something along the line of “Lead software engineer”

Margaret Hamilton was born in rural Indiana in 1936. Her father was a philosopher and poet, who, along with grandfather, encouraged her love of math and sciences. She studied mathematics with a minor in philosophy, earning her BA from Earlham College in 1956. While at Earlham, her plan to continue on to grad school was delayed as she supported her husband working on his own degree from Harvard. Margaret took a job at MIT, working under Professor Edward Norton Lorenz on a computer program to predict the weather. Margaret cut her teeth on the desk-sized LGP-30 computer in Norton’s office.

Hamilton soon moved on to the SAGE program, writing software which would monitor radar data for incoming Russian bombers. Her work on SAGE put Margaret in the perfect position to jump to the new Apollo navigation software team.

The Apollo guidance computer software team was designed at MIT, with manufacturing done at Raytheon. To say this was a huge software project for the time would be an understatement. By 1968, over 350 engineers were working on software. 1400 man-years of software engineering were logged before Apollo 11 touched down on the lunar surface, and the project was lead by Margaret Hamilton.

Margaret was still considered a beginner programmer when she started work on the Apollo program. As you might expect, she was given a very low priority task: write software that would run in the event of an abort. This was software that would be used for one of the early tests, so no one expected the abort code to be run. Margaret even named the program “forget it”. Margaret was an instant expert, called into NASA to explain how her software worked, and answer questions.

Eventually, Margaret became the lead programmer for the guidance computer. She was not a hands-off manager though — she was very much in the trenches, working to get men to the moon and back again. By this time she was also a working parent. During the many late night and weekend work sessions, she would bring her daughter Lauren in. Margaret would run tests, and “play astronaut” and Lauren would play along with her.

During one test session, Lauren entered something at the controls. The guidance computer immediately crashed, bringing the whole system down. Margaret investigated and found that Lauren had inadvertently loaded up the P01 pre-launch program while the command module was in flight. If an astronaut did this during a mission, it would be disastrous, as the P01 program would erase all the computers navigation data. The ship would be flying blind.

Margaret suggested adding software to prevent this from happening, but NASA denied her request. More software means more possible bugs. A real astronaut would never, ever load the pre-launch program while the mission was underway.

To appease Margaret, NASA added a user note to the software: “Do not select P01 during flight”

During Apollo 8, Astronaut Jim Lovell proved NASA wrong by accidentally loading up P01 on the 5th day of the mission. The system crashed, and the navigation data was lost. Margaret and her team were called in to save the day. They spent eight hours studying the software and verifying a method of recovery. It had to work, and it had work the first time. Following Margaret’s instructions, NASA uploaded new navigation coefficients and the mission was able to continue.

Even though software was driving the Apollo program, it still wasn’t considered a science – at least not by the hardware or mechanical engineers. Programmers were held to a lower regard. To combat this, Margaret coined the term “software engineering”. Many of her co-workers considered it a joke at first. Of course, time has shown that she was absolutely right.

Margaret and the entire software team knew that they were doing something that had never been done before — creating man-rated software that had to be perfect the first time it was used. Any major bug would mean death for the astronauts trusting their lives to the software. Margaret was especially worried about computer problems going unnoticed by the astronauts until it was too late. She met with NASA officials and together they came up with a way to inform the astronauts that the computers were having problems.

These warnings didn’t take long to show up. During the landing sequence of Apollo 11, 1201 and 1202 program alarms lit up the cockpit several times. These were Margaret’s warnings. They indicated that the computer had run out of resources and was restarting, shedding low priority tasks to concentrate on the tasks important for the landing phase of the mission. These alarms should never have sounded — the fact that they showed up meant something was very wrong. However, the team at mission control knew how robust Margaret’s load shedding system was, so the astronauts were told to ignore and clear the alarm.

Investigations later showed that the 1201 and 1202 alarms were caused by a checklist error. The checklists instructed the astronauts to turn on their rendezvous radar during the landing phase of the mission. The rendezvous radar wasn’t needed for landing, yet it since it was on, it was still interrupting the guidance computer many times each second. These interruptions would cause the computer to run out of resources, and display one of Margaret’s alarms. If the software hadn’t been written and tested so well, the load of from the extra radar data could have caused the LEM to abort the mission, or worse, crash into the moon — stranding or killing the astronauts onboard.

Margaret continued working at MIT on NASA programs well after the Apollo missions. She worked on Skylab as well as the first revisions of the software for the space shuttle. Eventually, though, she left to start her own company.

While working on Apollo, Margaret found many bugs and squashed them. She carefully documented and categorized each of these. That work allowed her to recognize that many bugs occur at the boundaries between software modules. From there, Margaret was able to derive six mathematical axioms for software design. At Higher Order Software, Margaret created Universal Systems Language to put these axioms into practice.

Today Margaret is CEO (and founder) of Hamilton Technologies, Inc, where she is still creating tools and systems to make software safer and more bug-free.

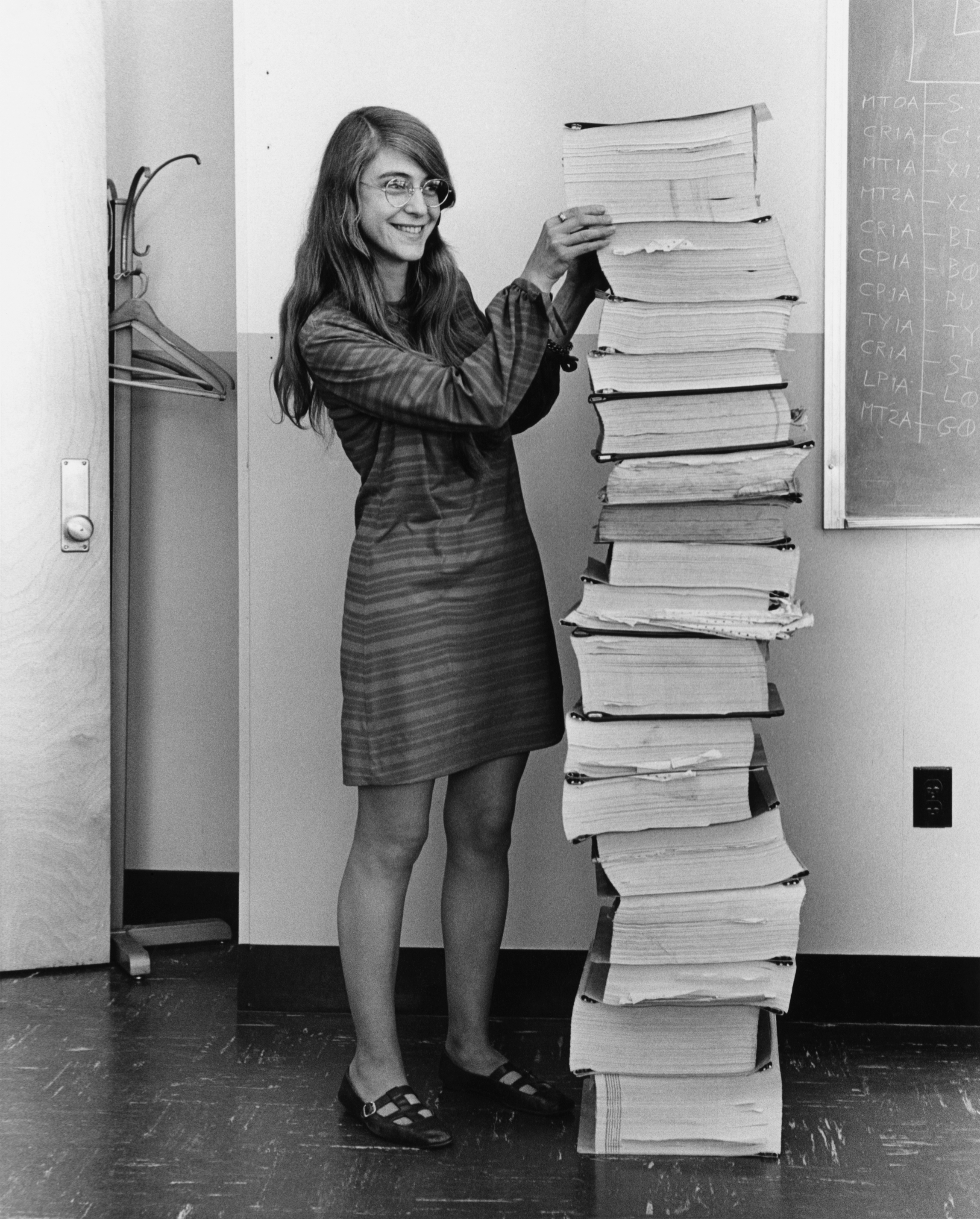

For many years Margaret was well known within the inner circle of NASA and MIT engineers and scientists. However, she wasn’t known to the general public. An image of her standing next to a stack of printouts taller than her — the entire source of the Apollo guidance computer changed all that. Margaret is now deservedly known as one of the first women in software engineering and has been honored with a Presidential medal of freedom, as well as being included in the Women of NASA LEGO set depicting her famous image.